By Tilda Joy Blackbourn-Rooney – A ‘Special Project’ (SCOM3005, 2025, shortened)

Communicating Extinction through Children’s Picture Books

This report is part of an environmental science communication project developing a picture book aimed at 3-7 year olds.

Children are experiencing reduced interaction with biodiversity compared to previous generations, as a result of increasing urbanisation and developing technologies (Chawla, 2020). Art and media have an important role to play in filling this gap (Kesebir and Kesebir, 2017). Picture books are one art form that is uniquely positioned to target children early, and have been widely accepted as a tool for childhood education (Crawford, Roberts and Lacina, 2024). In particular, picture books have been found to be an effective tool for promoting environmental awareness in primary school students (Aurélio et al., 2021). They are also a meaningful science communication method, using the power of storytelling and visual art to bring life to scientific concepts (Peters, 2024). In addition to reaching children, picture books also come with secondary audiences such as parents and educators who may purchase and assist in reading the book.

The challenges of extinction stories

In addition, often threatened species are unknown to children because their low numbers mean they are rarely seen in real life. It can also be difficult to communicate the kind of grief that comes with collective loss, compared to the death of an individual. In his book Flight Ways (2016), Thom van Dooren discusses the need for extinction stories to reject human exceptionalism (Van Dooren, 2016). He outlines the need to not portray humans as separated from and superior to the rest of nature. Instead of focussing on how saving a species may directly benefit people and the economy, Dooren argues for ‘lively extinction stories’ focussed on entanglement. By this he refers to stories that show how a species is entangled and relates to the world around it. He also notes a trend of extinction stories focussing only on the last survivor of a species, and reflects on how what makes a species a species (its behavior and entanglements) are often lost far sooner than this point.

These considerations all contribute to my own extinction story, shaping its focus.

Extinction and picture books

Picture books often portray biodiversity, however, research calls for a more diverse representation of species (Hooykaas et al., 2022; Ritchie and Umbers, 2024). Exotic and domestic species often dominate children’s literature, meaning that in Australia, children experience more stories about bears, honey bees, and squirrels, than native species (Ritchie and Umbers, 2024). This is an issue because people tend to care about things that they know, and if people do not experience local species in literature from a young age, it may be harder for them to empathise with them later in life (Schlegel and Rupf, 2010). Conversely, by portraying native species in children’s books, we can raise interest, knowledge and empathy surrounding that species, which can impact future pro-conservation behaviours (Hooykaas et al., 2022). Pro-conservation behaviours are essential, as Australia has one of the most severe mammal extinction rates, with over 10% of endemic terrestrial species going extinct across in last two centuries, and 21% of remaining endemic mammals assessed as threatened (Legge et al. 2023; Woinarski et al. 2015). Picture books have also been found to help children consider the implications of human exceptionalism, and think about how to coexist with other species (Suh, 2022). It is also an important age to communicate extinction stories as children are more likely than adults to consider the intrinsic value of animals, rather than how they benefit humans (Born, 2018).

My Picture book

In the context of rapid, global biodiversity declines, this project narrows the environmental science scope to focus on extinction (Roe, 2019). In particular, it is driven by the question of ‘how to communicate extinction to children?’, which comes with a variety of unique challenges. These challenges include the delicate subject of death, how to communicate the large scale and timelines extinction occurs over, and how to maintain a sense of hope in the face of depressing realities.

My extinction story is based on the Eastern Quoll ( Dasyurus viverrinus ) which is listed as endangered under the EPBC (Threatened Species Scientific Committee, 2015). I chose this species as they experienced a local extinction on mainland Australia in the 1960s, but have recently been the focus of successful conservation efforts, reintroducing genetically diverse Tasmanian individuals to the mainland to restore ecosystems and create insurance populations (Wilson et al., 2023). In this way, the story of the Eastern Quoll contains the emotional depth that comes with extinction, while maintaining a hopeful message.

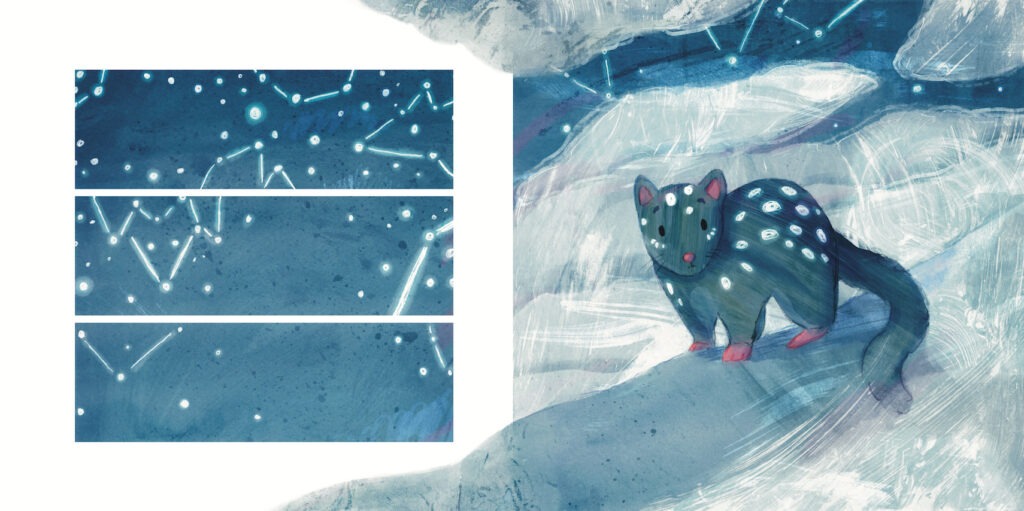

My picture book outcome, titled ‘Quoll and the Stars’, follows an individual quoll through her life in Tasmania. Although preferring solitude, she feels comforted by the presence of her species, which she sees through a visual metaphor of the stars. However, as the stars begin to disappear (reflecting declining population numbers from the mainland extinction), Quoll has to deal with grief, isolation, and feelings of collective loss. At the end of the book she chooses to follow conservation scientists overseas, and is part of the successful mainland reintroduction. Some of the stars begin to return to the sky, signaling hope for the species’ survival.

To combat mis-representation of science in picture books, Ritchie and Umbers (2023) call for picture book creators to engage with real scientists. As part of this project I reached out to Belinda Wilson who was the lead researcher on the Eastern Quoll reintroduction in Mulligans Flat Woodland Sanctuary. She provided me with a collection of resources related to her work which helped inform the story and endnotes. Although traditionally picture books do not include direct references, I have noted the resources at the end of this report, and intend to be in further contact and do more thorough fact-checking if the book ever reaches a publication stage.

Strategies to efficiently communicate extinction

Narrative

In her book, ‘Reimagining Your Nonfiction Picture Book’ (2023), Kirsten W. Larson discusses a variety of structures nonfiction communication can take. Some examples include:

● Cause-and-effect structure: cumulatively shows how a sequence of events unfold like dominoes. ● Circular structure: A book that begins where it ends, for example, Water is Water (Paul and Chin, 2015) by Miranda Paul about the water cycle). ● Question-and-answer structure: asking the reader rhetorical questions then revealing the answer on the page turn.

However, for my book I have chosen a traditional narrative structure as I feel it is more suited to the emotional nature of the topic. Narrative can evoke emotion in an audience and is a powerful science communication tool (Dahlstrom, 2014). It moves beyond facts, and makes people care (Joubert, Davis and Metcalfe, 2019). In my story, Quoll follows a traditional hero’s arc. She lives her everyday life, is confronted with a problem, attempts to comprehend and solve the problem, reaches her lowest moment, and then takes action towards a solution. This gives her relatability and anchors the story to a series of emotional beats. One consequence of this story structure is that the timeline of the books does not realistically align with the much longer sequence of events in real life. However, I find this an acceptable cost in exchange for the story remaining in Quoll’s perspective.

Hope

Many picture books tend to be aimed towards a slightly higher age bracket than the target audience of this project. Additionally, research shows that hope is a powerful tool in environmental communication (Chawla, 2020; Ojala, 2011). Without it, children can fall into feelings of helplessness, avoidance, or nihilistic acceptance, which result in inaction. However, when children feel confident they can address environmental challenges and are given hope, they are more motivated to take action (Chawla, 2020). For these reasons, my story alludes to the impacts of successful Eastern Quoll mainland reintroductions, and ends on a hopeful note of stars beginning to return to the sky. It also recommends actions suitable for children in the endnotes.

Metaphor

I chose to use the visual metaphor for the stars to represent population decline, as metaphor has been found to make scientific subjects more accessible and engaging (Farinella, 2018). This literary strategy also helps to avoid more graphic representations of death, while still carrying an emotional impact. It also makes it easier to represent the scale of the problem.

Cuteness

Another reason I chose the Eastern Quoll is because of its cute appeal. They are fluffy, charismatic, have memorable spots, and are small enough to be non-threatening to humans (Marcus et al., 2017). Appealing to these characteristics and translating them into the drawing style, is another science communication method to evoke an immediate emotional response (Lubbe, 2022). This technique has drawbacks, as its popularity in both children’s books and wider extinction stories can reinforce human bias and preferences towards conserving cute species, leaving less-charismatic species unsupported (Wallace, 2021; Hooykaas et al., 2022).

Animal perspective and level of anthropomorphism

Many of the environmental children’s picture books I read for this project focus on a child protagonist that goes through a journey to save an animal. From this the reader reflects the human protagonist, learning about the problem and solution alongside them. However, I wanted my story to be from the animal’s perspective in an attempt to move further away from human exceptionalism. Inspired by Dooren’s (2016) reflections, I tried to include pages showing Quoll entangled in her natural environment contributing to her ecosystem through hunting. I also used less words than a traditional picture book, even including some wordless spreads, to better portray how Quoll might be experiencing the world. I also tried to keep the anthropomorphism in the story subtle. Subtle anthropomorphism can increase ecological knowledge and empathy (McCabe and Nekaris, 2019). However, when taken too far it can also lead to confusion in children between what is fact and fiction (Strouse, Nyhout and Ganea, 2018). While Quoll does not behave completely like a normal Eastern Quoll, she remains on the opposite end of the spectrum to caractured animals that wear human clothes and have human names.

Considerations and next steps

For this project I completed the first draft and storyboard of my picture book manuscript, with a completed cover and 4 fully illustrated spreads. The next step for this project is to let it sit and then revisit it with fresh eyes to edit. I also intend to seek informal feedback from industry professionals and young children to evaluate and improve the outcome. This will also help improve my ability to pitch the manuscript to publishers and increase the marketing appeal of the book. As I am using an endemic Australian species, and star metaphor, I also feel it is important to consider any potential overlap with Indigenous Australian knowledge and stories. Indigenous Australians have a long history with astronomy (Noon and Napoli, 2022). I have only found one recorded story from the Potaruwutj people in the Southeast of South Australia, who consider a male ancestor of the Quoll to be the moon (Mitjan) (Clarke, 2015). However, for future development of this book I would like to do more research on this aspect. Another future research option is to move beyond cute, charismatic animals discussed previously and tackle the challenge of extinction stories about ugly or unremarkable creatures like insects and plants. I have also been inspired by this project and the reflection of Dooren (2016) to begin a story of entanglement in endangered Australian ecosystems, and how they respond to changing fire regimes.