By Sarah Barnes – An interdisciplinary SCOM6004 Science Communication Internship Project (2023)

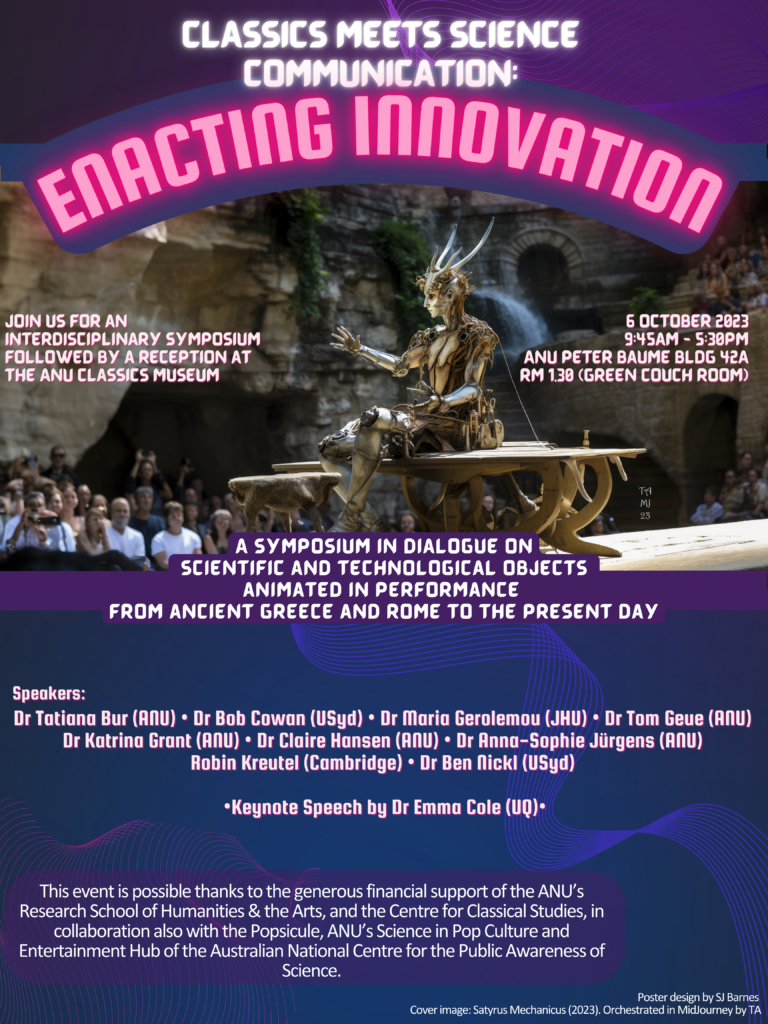

Sarah’s “Enacting Innovation” poster series is a creative science communication project: an artistic, visual interpretation of the interdisciplinary ‘Classics meets SciComm’ conference “Enacting Innovation” (organised by Dr Tatiana Bur and Dr Anna-Sophie Jürgens) which brought together academics from Classical Studies, Science Communication and Pop Culture Studies to think about how objects were and are technologically animated in theatrical contexts, both as ideas in text and as realities in production, from Classical antiquity to the present day.

Throughout these descriptions of research and discussions of cultural history in the near and very distant past, I was struck by a number of unintended themes that didn’t so much weave through Enacting Innovation as entangle it. First, a reoccurring sense distrust or fear of novel inventions, be they forms of theatre and oration that differed previous generations or humanoid automatons that drive questions of what it means to be human and have agency. And second, questions of who is remembered by history and how we can be more active in choosing to find the evidence of the often enslaved technicians and performers so often left out of historical records of theatre, technology, and innovation despite their incredible contributions.

These reflections also mirrored my own experience in working with TA to create the AI artworks that accompanied each speaker on that day and which head each page of this artistic reflection. I am one of those people whose gut reaction to generative AI was one of unease and antipathy, initially hung on the idea that it isn’t “the same” as creating art through traditional means. But what even are traditional means? Did I mean AI images weren’t the same as oil paintings? Sure, but neither are photographs. And digital paintings aren’t the same as physical mediums either, but I’d never say they aren’t art. Through this internship and in experiencing the symposium I’ve re-adjusted my perspective. Generative AI is a tool, and like any tool, it takes skilled hands to take raw materials and make them into art.

That being said, generative AI is still a tool that uses real resources and creates real concerns for people around the world. Reports of unlicensed use of artwork in the learning databases, underpaid labour and excessive resource waste with OpenAI (the company behind ChatGPT and Dall-E), and issues around labour disputes in writing rooms throughout the TV and film industries should not be ignored. The companies that create these tools and the massive corporations that profit off of them need to be held accountable. A tool is not inherently harmful, but that doesn’t mean its wielders are inherently benign.

I’m so grateful to TA for lending us his technical expertise and artistic eye to create these AI artworks for us, and grateful to Anna-Sophie and Tatiana for giving me the privilege of facing those knee-jerk reactions head on. Only after unpacking all of the emotions that AI evoked for me and looking at what remained was I able to decide for myself which ones were worth holding onto, and which had been holding me back. And finally, I’d like to thank Abigail Hils, CPAS’s incredible Communication Officer for all her support and enthusiasm for my project both during the event itself and in the weeks following. Without her additional expertise, and the funding provided by the CPAS Critical Events Grant, this project would never have been half as vibrant and thought-provoking as it has turned out.

Abstracts, Speakers and Respondents

Dr Tatiana Bur, Australian National University, Centre for Classical Studies

ABSTRACT│ Ancient Greek vessels ‘enacted’ their own presence, their own function, their own theatricality in various ways. A subcategory of ancient vessels contained pneumatic enhancements so that they could perform playful tricks on those gathered around at the ancient drinking party (symposium). This paper will look at these performing pots, thinking through what they add to our understanding of the ancient symposium, on the one hand, and of the ancient science of pneumatics (the systematic study of the effects of running liquid, air, and steam), on the other. From there, I will scratch the surface of an entangled and important issue: the involvement of enslaved agents in said pneumatic performance, and the possible social repercussions. Taken together, these two strands lead me to ask how we should think about the combination of the innovative, performing pot, and the enslaved hand that seized the clay?

Dr Emma Cole, The University of Queensland, School of Communication and Arts

ABSTRACT │ In this talk, I introduce the role of Greek tragedy in three theatrical adaptations that I have collaborated on in recent years. Punchdrunk’s Kabeiroi (2017) was a geolocative, six-to-eight-hour experience based upon a fragmentary Aeschylean tragedy, while Medea in Exile, a trilogy written with Australian playwright Tom Holloway, took inspiration from fragments and iconographic evidence to tell Medea’s story beyond her act of infanticide. Finally, The Burnt City (2022-23, again with Punchdrunk) turned two Greek tragedies into an immersive world which collided the fall of Troy with dystopic science fiction for a roaming audience of up to 600 spectators per night. In each piece of classical reception, my collaborators and I sought to de-pedastalize the classics and innovate with theatrical form. Yet the spirit of innovation that we applied to our source texts can also be found within them; understanding ancient drama as a radical, experimental form of performance liberates practitioners to create theatrical practice anew.

Dr Robert Cowan, University of Sydney, Department of Classics and Ancient History

ABSTRACT │ Of all the genres of Ancient Greek drama, satyr play had the most explicit, sustained, and elusive engagement with innovation and technology. It manifests an ambivalent attitude to technology that reflects the wider Greek ambivalence about both technological innovation and theatrical illusion, as well as the genre’s own ambivalent depiction of its defining satyric chorus. Technology in the world of the play and in its performance is a genuine source of wonder (thauma) for the audience in the Theatre of Dionysos and for the satyric audience in the orchestra which focalizes their reactions, but that reaction is also mocked as a naïve response to trickery. Likewise, technology’s employment—again, by actors and by characters—can be a potent means of embodying the wondrous and the divine or a crude, theomachic burlesque. The contradictory status of the satyrs as primitive and resourceful, divine and bestial, self and other amplifies the contradictory status of the theatrical and non-theatrical technology with which they interact.

Dr Maria Gerolemou, Johns Hopkins University, Classics Department

ABSTRACT │ For centuries, technology has played a crucial role in theater, blurring the line between reality and representation. In ancient times, simple devices like masks, cranes, and moving set pieces fascinated audiences, expanding what could be seen and heard on stage. However, ancient texts warn that technology can stifle the audience’s imagination and creativity. Effective use of technology requires skilled technicians, as misuse can harm the artistic vision and diminish the performance’s impact. In this talk, I’ll showcase instances of technology enhancing visual and vocal portrayal in ancient Greek theater, and explore how it shaped the concept of mimesis while raising concerns in classical antiquity.

Dr Anna-Sophie Jürgens, ANU, Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science

ABSTRACT │ This presentation will take a closer look at the “Human or Machine?” performance routine – a once popular, now forgotten form of entertainment (and, potentially, a fascinating expression of ‘inverse mimesis’?). Concentrating on rare historical materials, this talk uncovers how “Human or Machine?” performances looked like and how they built on and added to the early twentieth-century cultural discourse, and trope, of the human machine. Extending the notion of popular modernism/modernity this talk will provide a better sense of the stories, cultural work, and aesthetic achievements emerging from the interplay of popular arts and (imaginaries of) technology, and clarifies how the braiding of (an idea of) machinery and clowning contributed to creating new comic forms.

Robin Kreutel, Cambridge University, Faculty of Classics

ABSTRACT │ Compared to the Greek world, the theatrical scene in republican Rome is often imagined as strikingly lacking in sophistication. There were no permanent theatre buildings for roughly 200 years, actors and playwrights were socially stigmatised and disenfranchised, and the Italic stage tradition before Rome’s turn to Greek literature is thought to be centred around improvisation rather than theatrical expertise. I will argue in this paper that our search for cultural innovation in early Roman drama should not be primarily focused on modern conceptions of innovation (science, technology), but ask what was innovative about the specific situation of early Roman drama. I will take a close look at Plautus’ palliata comedy and ask how the earliest non-fragmentary Latin author exploits the medium of language as a technology for cultural innovation. Zooming in on salient lexemes (ludus, machina, faber, architectus,…), I will show how he systematically manipulates established meanings of words to create a cultural space for himself as a language artist – a new social type in Rome’s swiftly changing mid-republican society.

Dr Ben Nickl, University of Sydney, Department of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies

ABSTRACT │ Canned laughter, or mechanically and by now digitally replicated glee, is a ubiquitous yet often under-researched phenomenon of entertainment media production. The objects that have mediated it, such as the so-called ‘laugh-box’, have long been a subject of curiosity and debate. This paper delves into the intricate web of cultural, technological, and sociological factors that underlie the use of canned laughter. By examining the historical evolution of this phenomenon, from its early days to contemporary digital culture objects and online applications, we can uncover its multifaceted role in shaping audience and user perceptions of humour as well as content that triggers emotional responses. Through an interdisciplinary lens, we can also unravel some of the cultural mechanics behind canned laughter, offering valuable insights for media producers, sociologists, and those interested in cultural technologies of feeling. Such findings have broader implications for understanding the complex interplay between media, culture, and our sense of humour, ultimately shaping our understanding of how laughter is both constructed and deconstructed in the modern entertainment landscape and located at the same time within and outside the human.

Dr Tom Geue, ANU, Lecturer in Classics

Tom Geue teaches Latin at the Australian National University. His 2019 book, Author Unknown, proposed some new ways of working with anonymous authorship. His new book, forthcoming with Verso Books in 2024, is an intellectual biography of the Italian classical philologist and Marxist Sebastiano Timpanaro (1923-2000).

Dr Estelle Strazdins, ANU, Lecturer in Classics

Estelle’s research revolves around Greek literature and material culture of the Roman Imperial period and early European travellers to Ottoman lands. Her first monograph, Fashioning the Future in Roman Greece: Memory, Monuments, Texts, was published by OUP in 2023.

Dr Claire Hansen, ANU, Lecturer in English

Claire specialises in Shakespeare studies and has also published on Christopher Marlowe, education, early modern dance, and female characters in renaissance literature. Claire’s current projects include place-based approaches to Shakespeare, Shakespearean blue humanities, and the health humanities. Claire is passionate about theatre, and has published a host of theatre reviews on The Conversation and on the Shakespeare Reloaded blog.

Reception – Classics Museum

Sarah Barnes, ANU, Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science

BIO & ABSTRACT │ Sarah is a Master student in Science Communication at the Australian National University with an interest in how science is communicated in online spaces by expert scientists and amateur content creators. In their short presentation, Sarah will be discussing how they put their critical thinking skills to work while collaborating with an AI artist on the images used throughout this event.

Dr Ehsan Nabavi, ANU, Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science

BIO & ABSTRACT │ Ehsan is a Senior Lecturer at the Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science and the Head of the Responsible Innovation Lab (RI Lab) at the Australian National University. As an engineer-sociologist his research explores the intersection of technology and society. In his short presentation, Ehsan will introduce the mission and work of the RI Lab.